The Violet Nurseries of Henfield,

West Sussex (1899-1952)

Between 1898 and 1952 the village of Henfield in West Sussex was home to six pioneering women, who moved there to begin new lives. Over the course of fifty years this group of family and friends helped to revolutionise their respective fields of sculpture, horticulture, theatre, women’s suffrage, and medicine. They defied class, turned their backs on wealth and status, and created the first political Women’s Institute.

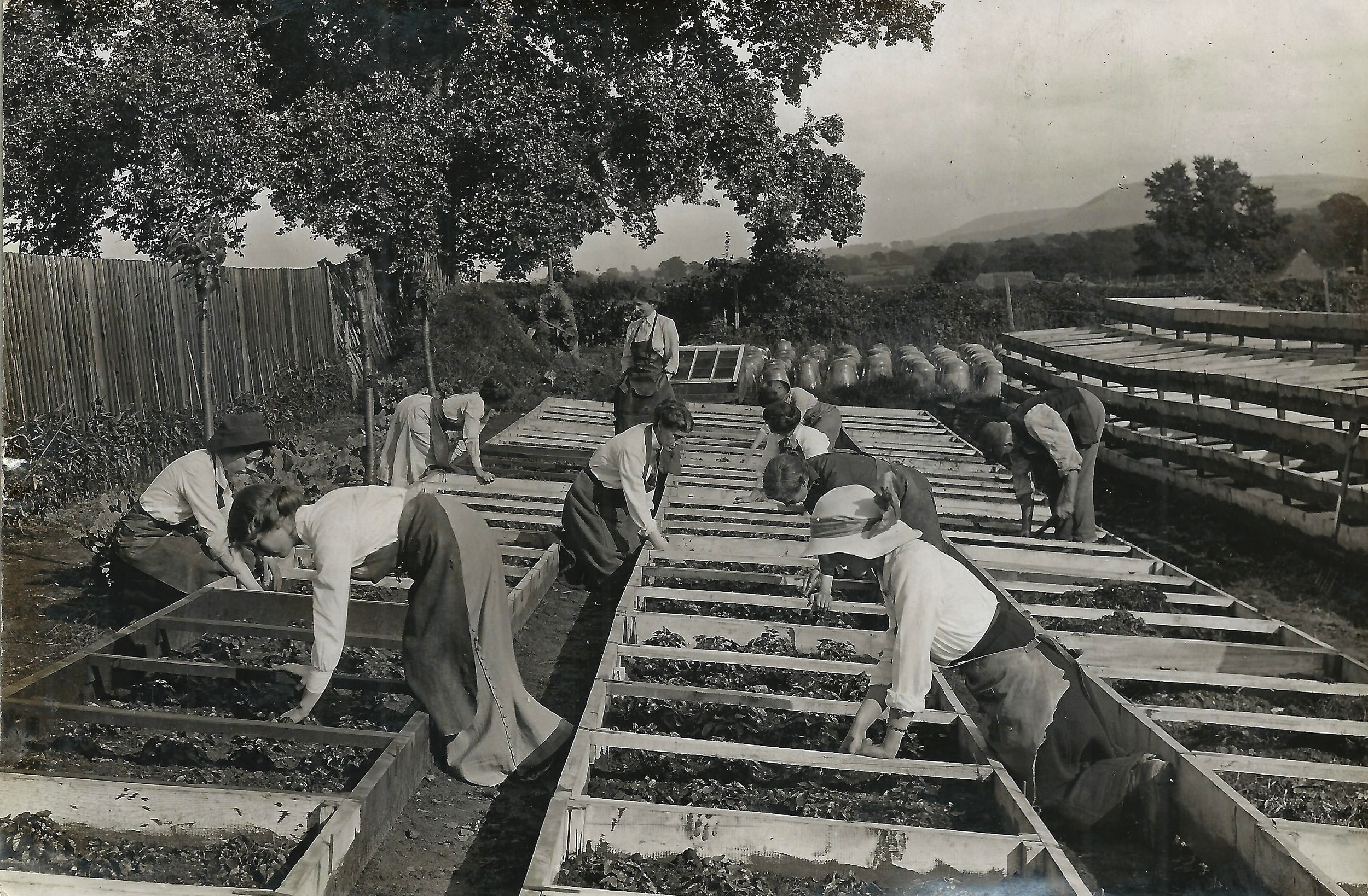

At the heart of their network was the Henfield Violet Nursery founded in 1900 by Ada Brown and Decima Allen, and modelled upon the philosophy of the nineteenth century social reformer, advocate of women’s freedom, and LGBT rights pioneer Edward Carpenter. As fellows of the Royal Horticultural Society, the Misses Allen-Brown introduced new varieties of violet into England at this time from France. They taught women the art of French Horticulture, and in 1905 had a resident French expert instructing the students. When violets became the emblem of the women’s suffrage movement the Nurseries played a defining role in promoting women’s independence.

The people connected with the Henfield Violet Nurseries were radical thinkers, people who broke with convention and wished to do something different with their lives. As historian Elizabeth Crawfurd pointed out several years ago, Decima and Ada spoiled their 1901 census form, which suggests a deliberate act of rebellion against the state.

Their homemade Allen-Brown toiletries and scented products were made with perfume from the flowers grown on their land – a hundred years before “slow living” and “sustainable horticulture” emerged as models of environmental living. These products, advertised in magazines such as the Bystander, the Sphere, the Queen, and Votes for Women, became highly esteemed additions to the Edwardian lady’s wardrobe, and were endorsed and patronised by high-profile figures such as the Duchess of Sutherland and Queen Alexandra. Decima was also a Fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society. The Henfield Violet Nursery endured two world wars, and was a permanent feature of the village for fifty years.

As a child growing up in Henfield, only a mile or so from the site of the Violet Nurseries, I had missed their era by just a decade or so. The last of their circle, Dr. Octavia Wilberforce died in 1963. One of her legacies was Backsettown, a beautiful Tudor house that was owned by her lifelong partner the actor, campaigner, and writer Elizabeth Robins and developed by the women into a rest home for overworked professional women. As well as running her own practice from Brighton, Dr. Wilberforce was the medical supervisor of Backsett.

“The cemetery is alive with birdsong. I walk along the central avenue in sunshine far too warm for April, past a yew, disturbing a woodpigeon with a sudden flutter of wings. Rows of graves, divided by hedges and trees, occupy a large plot of several acres with an aged oak tree in the centre. I soon find what I am looking for – a weathered stone cross by a hedge on the northern boundary. Scattered amongst the russet leaves of last autumn are little dots of colour – the first wild violets of spring. I crouch down, brush away tendrils of spring grass to read: FLORENCE FLEMING NEE MIDWOOD. DIED 28TH MARCH 1919. Then, immediately above: GENE BROWN. DIED 22ND MAY 1915. Not far away lies another grave, with the names of two women from different families: Rachel Dyce Sharp and Decima Allen.

Nearby are the graves of Florence’s nephew Malcolm and niece Hilda, the children of John Dewhurst Milne of Cheshire and Lucy Midwood. A blackbird hops onto a nearby gravestone with a flick of his tail, reminding me that the names Midwood and Dewhurst are redolent of English fields and woods. ‘Hurst’ comes from the Anglo-Saxon word for cleared woodland, while ‘Midwood’ gives the impression of being cocooned by trees, wrapped in wooded hush, miles from any road or industry. Yet these names have more modern associations, far removed from their rustic origins – Milne of Cheshire was a founder of Britain’s first department store, and the Midwood’s of Manchester were some of Britain’s wealthiest cotton merchants. The Industrial Revolution, characterised by a shift from methods of hand production to machine, began in Britain 30 years before the rest of the world, and cotton manufacturing was a key player. The women of Henfield, who lived in the village from 1898–1952, rebelled against commercial manufacturing and all that it stood for by hand-making their products, and offering work and training to young women. This was in stark contrast to the shipping and cotton trades, founded upon slave labour, which had underpinned their families’ wealth. Their work was part of an Edwardian back to the land movement that sought to regenerate fading cottage industries. Henfield, perhaps more than any other Sussex village, was an ideal place – where women could be themselves and nurture their creative abilities. The warm air and loamy soil of Henfield has always been good for growing. The dry timbered walls of its old houses, irregularly shaped and sunken with time, textures and shapes, invite the creative mind. These interiors of quiet cold stone, with nooks and crannies, have a presence that shapes the lives of the people who live in them.” - Extract from my unpublished memoir.

In 2022 I wrote up my discoveries in an article for Garden History, the journal of the Gardens Trust, which was published in the summer edition of 2023. The full article can be downloaded without charge by clicking the button below.

Women working the violet beds using the French method of horticulture. The glass belljars, or ‘cloches’, are visible in the background.

Decima Allen with Jerry the pony, 1912.

In the distance is the South Downs and the rise of Wolstanbury Hill.